API Suppliers

US DMFs Filed

CEP/COS Certifications

JDMFs Filed

Other Certificates

0

Other Suppliers

USA (Orange Book)

0

Europe

0

Canada

Australia

South Africa

Uploaded Dossiers

U.S. Medicaid

0

Annual Reports

0

1. L Valine

2. L-valine

1. L-valine

2. 72-18-4

3. (s)-valine

4. H-val-oh

5. (s)-2-amino-3-methylbutanoic Acid

6. (2s)-2-amino-3-methylbutanoic Acid

7. 2-amino-3-methylbutyric Acid

8. (s)-2-amino-3-methylbutyric Acid

9. L-alpha-amino-beta-methylbutyric Acid

10. Valinum [latin]

11. Valina [spanish]

12. Valine (van)

13. Butanoic Acid, 2-amino-3-methyl-

14. Valine [usan:inn]

15. L-valin

16. Valine, L-

17. L(+)-alpha-aminoisovaleric Acid

18. (s)-alpha-amino-beta-methylbutyric Acid

19. 7004-03-7

20. Butanoic Acid, 2-amino-3-methyl-, (s)-

21. 2-amino-3-methylbutyric Acid, (s)-

22. 2-amino-3-methylbutanoic Acid, (s)-

23. Val

24. Nsc 76038

25. (l)-valine

26. 2-amino-3-methylbutanoic Acid (van)

27. Valine (l-valine)

28. Chebi:16414

29. L-(+)-alpha-aminoisovaleric Acid

30. L-2-aminoisovaleric Acid

31. Nsc-76038

32. Valina

33. Hg18b9yrs7

34. L-val

35. Mfcd00064220

36. Valinum

37. (2s)-2-amino-3-methylbutanoate

38. L-2-amino-3-methylbutanoic Acid

39. Alpha-aminoisovaleric Acid

40. Einecs 200-773-6

41. 2-amino-3-methyl-butyric Acid

42. Unii-hg18b9yrs7

43. 2-amino-3-methylbutanoate

44. Racemic Valine

45. L-(+)-a-aminoisovaleric Acid

46. S-valin

47. (s)-alpha-aminoisovaleric Acid

48. L-(+)-.alpha.-aminoisovaleric Acid

49. L-a-amino-b-methylbutyric Acid

50. Hsdb 7800

51. 3h-l-valine

52. (s)-a-amino-b-methylbutyric Acid

53. L-valine;

54. L-valine, Fcc

55. Valine (usp)

56. (+)-valine

57. L-valine,(s)

58. 1t4s

59. L-valine (jp17)

60. L-valine, 99%

61. Valine [vandf]

62. Valine [hsdb]

63. Valine [inci]

64. Valine [usan]

65. (s)-val

66. L-val-4

67. L-val-oh

68. Valine [inn]

69. Valine [who-dd]

70. Valine [ii]

71. Valine [mi]

72. 2-amino-3-methylbutyrate

73. L-valine [fcc]

74. L-valine [jan]

75. Valine [mart.]

76. Bmse000052

77. Bmse000811

78. Bmse000860

79. Ec 200-773-6

80. L-(+)-a-aminoisovalerate

81. L-a-amino-b-methylbutyrate

82. Schembl8516

83. (s)-a-aminoisovaleric Acid

84. L-valine [usp-rs]

85. H-val-2-chlorotrityl Resin

86. (s)-?-aminoisovaleric Acid

87. 2-aminoisovaleric Acid,(s)

88. Chembl43068

89. Valine [ep Monograph]

90. (s)-a-amino-b-methylbutyrate

91. L-(+)-alpha-aminoisovalerate

92. L-iso-c3h7ch(nh2)cooh

93. Valine [usp Monograph]

94. Gtpl4794

95. (s)-2-amino-3-methylbutyrate

96. (s)-2-amino-3-methylbutanoate

97. Dtxsid40883233

98. L-alpha-amino-beta-methylbutyrate

99. (s)-2-amino-3-methyl-butanoate

100. Pharmakon1600-01301009

101. Zinc895099

102. Hy-n0717

103. (s)-alpha-amino-beta-methylbutyrate

104. (s)-2-amino-3-methyl-butyric Acid

105. Bdbm50463208

106. Nsc760111

107. S5628

108. (s)-2-amino-3-methyl-butanoic Acid

109. L-valine, 98.5-101.5%

110. Akos015841564

111. Am82363

112. Ccg-266067

113. Cs-w020706

114. Db00161

115. L-valine, 99%, Natural, Fcc, Fg

116. Nsc-760111

117. Ncgc00344520-01

118. As-12787

119. L-valine, Bioultra, >=99.5% (nt)

120. L-valine, Saj Special Grade, >=98.5%

121. Db-029989

122. L-valine, Reagent Grade, >=98% (hplc)

123. V0014

124. L-valine, Vetec(tm) Reagent Grade, >=98%

125. C00183

126. D00039

127. L-valine, Cell Culture Reagent (h-l-val-oh)

128. Lysine Acetate Impurity D [ep Impurity]

129. M02950

130. V-1800

131. (s)-(+)-2-amino-3-methylbutyric Acid

132. 064v220

133. Q483752

134. Q-100919

135. L-valine, Certified Reference Material, Tracecert(r)

136. F8889-8698

137. Valine, European Pharmacopoeia (ep) Reference Standard

138. Z1250208665

139. 1b39571b-0ae8-4a9a-ae80-4b898d11a981

140. L-valine, Dimer, Meets The Analytical Specifications Of Usp

141. L-valine, United States Pharmacopeia (usp) Reference Standard

142. L-valine, Pharmaceutical Secondary Standard; Certified Reference Material

143. L-valine, From Non-animal Source, Meets Ep, Jp, Usp Testing Specifications, Suitable For Cell Culture, 98.5-101.0%

144. L-valine, Pharmagrade, Ajinomoto, Ep, Jp, Usp, Manufactured Under Appropriate Gmp Controls For Pharma Or Biopharmaceutical Production, Suitable For Cell Culture

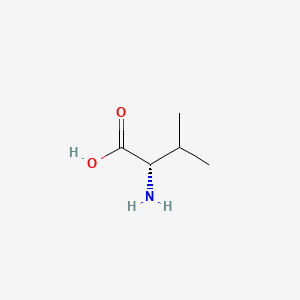

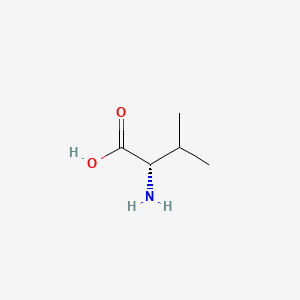

| Molecular Weight | 117.15 g/mol |

|---|---|

| Molecular Formula | C5H11NO2 |

| XLogP3 | -2.3 |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor Count | 2 |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor Count | 3 |

| Rotatable Bond Count | 2 |

| Exact Mass | 117.078978594 g/mol |

| Monoisotopic Mass | 117.078978594 g/mol |

| Topological Polar Surface Area | 63.3 Ų |

| Heavy Atom Count | 8 |

| Formal Charge | 0 |

| Complexity | 90.4 |

| Isotope Atom Count | 0 |

| Defined Atom Stereocenter Count | 1 |

| Undefined Atom Stereocenter Count | 0 |

| Defined Bond Stereocenter Count | 0 |

| Undefined Bond Stereocenter Count | 0 |

| Covalently Bonded Unit Count | 1 |

A branched-chain essential amino acid that has stimulant activity. It promotes muscle growth and tissue repair. It is a precursor in the penicillin biosynthetic pathway.

National Library of Medicine's Medical Subject Headings online file (MeSH, 1999)

It is used as a dietary supplement. It is also an ingredient of several preparations that have been promoted for disorders of the liver.

Sweetman SC (ed), Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London: Pharmaceutical Press (2009), p.1971.

Branched chain amino acid (BCAA)-enriched protein or amino acid mixtures and, in some cases, BCAA alone, have been used in the treatment of a variety of metabolic disorders. These amino acids have received considerable attention in efforts to reduce brain uptake of aromatic amino acids and to raise low circulating levels of BCAA in patients with chronic liver disease and encephalopathy. They have also been used in parenteral nutrition of patients with sepsis and other abnormalities.

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 705, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

The aim of this study was to evaluate the compliance of the diet with limited branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) content in long-term observation of patients with maple syrup urine disease (MSUD). The study group consisted of 7 children at age of 1.5-18 years. Nutrition evaluation was based on current diet records from 3-4 days, every 3-4 months. ... Energy and content of most of the nutrients in proposed daily products lists were in agreement with RDI except calcium. Diet analysis at MSUD children revealed insufficient contents of: iron, zinc, copper, vitamin B1, B2, niacin and vitamin C (often below 90% RDI). /Branched chain amino acids/

PMID:17711097 Kowalik A, et al; Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 58 (1): 95-101.

Assays of the amino acid levels in 5,888 newborns and 20 subjects ranging in age from 1 to 20 years, suspected of metabolic diseases, revealed a case of "maple syrup urine disease" caused by disorders in the intermediate metabolism of valine, whose serum and urinary concentrations were followed up from the first days of life. This patient also showed frequent episodes of hypoglycemia. An early treatment with polyvitamins, minerals and trace elements for 18 months resulted in the partial reactivation of the deficient enzymatic systems and the return to normal of the serum and urinary valine and glucose values. Administration of the same treatment to patients over one year of age ... was much less effective, thus supporting the conclusion that the vitamins and minerals could be useful in the "maple syrup urine disease" only if they were administered immediately after the disease onset ...

PMID:8081313 Mogos, T, et al; Rom J Intern Med 32 (1): 57-61 (1994).

Promotes mental vigor, muscle coordination, and calm emotions. May also be of use in a minority of patients with hepatic encephalopathy and in some with phenylketonuria.

L-valine is a branched-chain essential amino acid (BCAA) that has stimulant activity. It promotes muscle growth and tissue repair. It is a precursor in the penicillin biosynthetic pathway. Valine is one of three branched-chain amino acids (the others are leucine and isoleucine) that enhance energy, increase endurance, and aid in muscle tissue recovery and repair. This group also lowers elevated blood sugar levels and increases growth hormone production. Supplemental valine should always be combined with isoleucine and leucine at a respective milligram ratio of 2:1:2. It is an essential amino acid found in proteins; important for optimal growth in infants and for growth in children and nitrogen balance in adults. The lack of L-valine may influence the growth of body, cause neuropathic obstacle, anaemia. It has wide applications in the field of pharmaceutical and food industry.

Absorption

Absorbed from the small intestine by a sodium-dependent active-transport process.

Blood and tissue concentrations of branched chain amino acids (BCAA) are altered by several disease and abnormal physiological states, including diabetes mellitus, liver dysfunction, starvation, protein-calorie malnutrition, alcoholism, and obesity. These and other conditions sometimes produce drastic alterations in plasma pools of BCAA. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 704, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

Although the free amino acids dissolved in the body fluids are only a very small proportion of the body's total mass of amino acids, they are very important for the nutritional and metabolic control of the body's proteins. ... Although the plasma compartment is most easily sampled, the concentration of most amino acids is higher in tissue intracellular pools. Typically, large neutral amino acids, such as leucine and phenylalanine, are essentially in equilibrium with the plasma. Others, notably glutamine, glutamic acid, and glycine, are 10- to 50-fold more concentrated in the intracellular pool. Dietary variations or pathological conditions can result in substantial changes in the concentrations of the individual free amino acids in both the plasma and tissue pools.

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 596, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

After ingestion, proteins are denatured by the acid in the stomach, where they are also cleaved into smaller peptides by the enzyme pepsin, which is activated by the increase in stomach acidity that occurs on feeding. The proteins and peptides then pass into the small intestine, where the peptide bonds are hydrolyzed by a variety of enzymes. These bond-specific enzymes originate in the pancreas and include trypsin, chymotrypsins, elastase, and carboxypeptidases. The resultant mixture of free amino acids and small peptides is then transported into the mucosal cells by a number of carrier systems for specific amino acids and for di- and tri-peptides, each specific for a limited range of peptide substrates. After intracellular hydrolysis of the absorbed peptides, the free amino acids are then secreted into the portal blood by other specific carrier systems in the mucosal cell or are further metabolized within the cell itself. Absorbed amino acids pass into the liver, where a portion of the amino acids are taken up and used; the remainder pass through into the systemic circulation and are utilized by the peripheral tissues. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 599, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

Protein secretion into the intestine continues even under conditions of protein-free feeding, and fecal nitrogen losses (ie, nitrogen lost as bacteria in the feces) may account for 25 percent of the obligatory loss of nitrogen. Under this dietary circumstance, the amino acids secreted into the intestine as components of proteolytic enzymes and from sloughed mucosal cells are the only sources of amino acids for the maintenance of the intestinal bacterial biomass. ... Other routes of loss of intact amino acids are via the urine and through skin and hair loss. These losses are small by comparison with those described above, but nonetheless may have a significant impact on estimates of requirements, especially in disease states. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 600-601, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

For more Absorption, Distribution and Excretion (Complete) data for L-Valine (8 total), please visit the HSDB record page.

Hepatic

The branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) -- leucine, isoleucine, and valine -- differ from most other indispensable amino acids in that the enzymes initially responsible for their catabolism are found primarily in extrahepatic tissues. Each undergoes reversible transamination, catalyzed by a branched-chain aminotransferase (BCAT), and yields alpha-ketoisocaproate (KIC, from leucine), alpha-keto-beta-methylvalerate (KMV, from isoleucine), and alpha-ketoisovalerate (KIV, from valine). Each of these ketoacids then undergoes an irreversible, oxidative decarboxylation, catalyzed by a branchedchain ketoacid dehydrogenase (BCKAD). The latter is a multienzyme system located in mitochondrial membranes. The products of these oxidation reactions undergo further transformations to yield acetyl CoA, propionyl CoA, acetoacetate, and succinyl CoA; the BCAA are thus keto- and glucogenic.

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 704, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

Once the amino acid deamination products enter the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (also known as the citric acid cycle or Krebs cycle) or the glycolytic pathway, their carbon skeletons are also available for use in biosynthetic pathways, particularly for glucose and fat. Whether glucose or fat is formed from the carbon skeleton of an amino acid depends on its point of entry into these two pathways. If they enter as acetyl-CoA, then only fat or ketone bodies can be formed. The carbon skeletons of other amino acids can, however, enter the pathways in such a way that their carbons can be used for gluconeogenesis. This is the basis for the classical nutritional description of amino acids as either ketogenic or glucogenic (ie, able to give rise to either ketones [or fat] or glucose). Some amino acids produce both products upon degradation and so are considered both ketogenic and glucogenic. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 606, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

... An NMR analysis was performed to identify the (13)C-labeled metabolites that are generated by astroglia-rich primary cultures (APC) during catabolism of U-(13)C-valine and that are subsequently released into the incubation medium. The results presented show that APC (1) are potently disposing of the valine contained in the incubation medium; (2) are capable of degrading valine to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle member succinyl-CoA; and (3) release into the extracellular milieu valine catabolites and compounds generated from them such as U-(13)C-2-oxoisovalerate, U-(13)C-3-hydroxyisobutyrate, U-(13)C-2-methylmalonate, [U-(13)C]isobutyrate, and [U-(13)C]propionate as well as several TCA cycle-dependent metabolites including lactate.

PMID:19127430 Murin R, et al; Neurochem Res 34 (7): 1195-1203 (2009).

... Metabolism of branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) was investigated in cultured cerebellar astrocytes in a superfusion paradigm employing (15)N-labeled leucine, isoleucine, or valine. Some cultures were exposed to pulses of glutamate (50 uM; 10 sec every 2 min; 75 min in total) to mimic conditions during glutamatergic synaptic activity ... Incorporation of (15)N into intracellular glutamate from (15)N-leucine, (15)N-isoleucine, or (15)N-valine amounted to about 40-50% and differed only slightly among the individual BCAAs. Interestingly, label (%) in glutamate from (15)N-valine was not decreased upon exposure to exogenous glutamate, which was in contrast to a marked decrease in labeling (%) from (15)N-leucine or (15)N-isoleucine. This suggests an up-regulation of transamination involving only valine during repetitive exposure to glutamate. It is suggested that valine in particular might have an important function as an amino acid translocated between neuronal and astrocytic compartments, a function that might be up-regulated during synaptic activity.

PMID:17497675 Bak LK, et al; J Neurosci Res 85 (15): 3465-70 (2007).

The activities of key enzymes in the valine catabolic pathway - branched-chain aminotransferase, branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, methacrylyl (MC)-coenzyme A (CoA) hydratase (crotonase), and 3-hydroxyisobutyryl-CoA (HIB-CoA) hydrolase - were measured in normal and cirrhotic human livers. Unlike rat liver, which does not contain branched-chain aminotransferase, the aminotransferase activity in the normal liver was measurable and is increased somewhat in cirrhosis of the human liver. The total activity of branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex in the normal human liver was approximately 1% of that in rat liver, and 20% to 30% of the complex was in the active form in both normal and cirrhotic livers. Only the actual activity of the enzyme was significantly decreased by cirrhosis. These results suggest that human liver is less active than rat liver in the catabolism of branched-chain amino and alpha-keto acids. Activities of MC-CoA hydratase and HIB-CoA hydrolase in human liver were very high compared with that of branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex, suggesting an important role for these enzymes in catabolism of a potentially toxic compound, MC-CoA, formed as an intermediate in the catabolism of valine and isobutyrate. Cirrhosis resulted in a significant decrease in HIB-CoA hydrolase activity but had no effect on the citrate synthase activity, suggesting that the decrease in HIB-CoA hydrolase activity does not reflect a general decrease in mitochondria but that it may contribute to cellular damage that culminates in liver failure.

PMID:8938168 Taniguchi K, et al; Hepatology 24 (6): 1395-8 (1996).

(Applies to Valine, Leucine and Isoleucine)

This group of essential amino acids are identified as the branched-chain amino acids, BCAAs. Because this arrangement of carbon atoms cannot be made by humans, these amino acids are an essential element in the diet. The catabolism of all three compounds initiates in muscle and yields NADH and FADH2 which can be utilized for ATP generation. The catabolism of all three of these amino acids uses the same enzymes in the first two steps. The first step in each case is a transamination using a single BCAA aminotransferase, with a-ketoglutarate as amine acceptor. As a result, three different a-keto acids are produced and are oxidized using a common branched-chain a-keto acid dehydrogenase, yielding the three different CoA derivatives. Subsequently the metabolic pathways diverge, producing many intermediates.

The principal product from valine is propionylCoA, the glucogenic precursor of succinyl-CoA. Isoleucine catabolism terminates with production of acetylCoA and propionylCoA; thus isoleucine is both glucogenic and ketogenic. Leucine gives rise to acetylCoA and acetoacetylCoA, and is thus classified as strictly ketogenic.

There are a number of genetic diseases associated with faulty catabolism of the BCAAs. The most common defect is in the branched-chain a-keto acid dehydrogenase. Since there is only one dehydrogenase enzyme for all three amino acids, all three a-keto acids accumulate and are excreted in the urine. The disease is known as Maple syrup urine disease because of the characteristic odor of the urine in afflicted individuals. Mental retardation in these cases is extensive. Unfortunately, since these are essential amino acids, they cannot be heavily restricted in the diet; ultimately, the life of afflicted individuals is short and development is abnormal The main neurological problems are due to poor formation of myelin in the CNS.

Amino acids are selected for protein synthesis by binding with transfer RNA (tRNA) in the cell cytoplasm. The information on the amino acid sequence of each individual protein is contained in the sequence of nucleotides in the messenger RNA (mRNA) molecules, which are synthesized in the nucleus from regions of DNA by the process of transcription. The mRNA molecules then interact with various tRNA molecules attached to specific amino acids in the cytoplasm to synthesize the specific protein by linking together individual amino acids; this process, known as translation, is regulated by amino acids (e.g., leucine), and hormones. Which specific proteins are expressed in any particular cell and the relative rates at which the different cellular proteins are synthesized, are determined by the relative abundances of the different mRNAs and the availability of specific tRNA-amino acid combinations, and hence by the rate of transcription and the stability of the messages. From a nutritional and metabolic point of view, it is important to recognize that protein synthesis is a continuing process that takes place in most cells of the body. In a steady state, when neither net growth nor protein loss is occurring, protein synthesis is balanced by an equal amount of protein degradation. The major consequence of inadequate protein intakes, or diets low or lacking in specific indispensable amino acids relative to other amino acids (often termed limiting amino acids), is a shift in this balance so that rates of synthesis of some body proteins decrease while protein degradation continues, thus providing an endogenous source of those amino acids most in need. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 601-602, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html

The mechanism of intracellular protein degradation, by which protein is hydrolyzed to free amino acids, is more complex and is not as well characterized at the mechanistic level as that of synthesis. A wide variety of different enzymes that are capable of splitting peptide bonds are present in cells. However, the bulk of cellular proteolysis seems to be shared between two multienzyme systems: the lysosomal and proteasomal systems. The lysosome is a membrane-enclosed vesicle inside the cell that contains a variety of proteolytic enzymes and operates mostly at acid pH. Volumes of the cytoplasm are engulfed (autophagy) and are then subjected to the action of the protease enzymes at high concentration. This system is thought to be relatively unselective in most cases, although it can also degrade specific intracellular proteins. The system is highly regulated by hormones such as insulin and glucocorticoids, and by amino acids. The second system is the ATP-dependent ubiquitin-proteasome system, which is present in the cytoplasm. The first step is to join molecules of ubiquitin, a basic 76-amino acid peptide, to lysine residues in the target protein. Several enzymes are involved in this process, which selectively targets proteins for degradation by a second component, the proteasome. /Amino acids/

NAS, Food and Nutrition Board, Institute of Medicine; Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients). National Academy Press, Washington, D.C., pg. 602, 2009. Available from, as of March 10, 2010: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10490.html